【トピックス】

Modern Tools in the Discovery and Design of Biocatalysts

Uwe T. Bornscheuer

Greifswald Univ.

Abstract

Several major developments took place in the field of biocatalysis over the past few years. This includes directed evolution as an extremely useful tool for biocatalyst improvement, methods for accessing ‘non-culturable’ biodiversity from the metagenome, and progress in sequencebased biocatalyst discovery from databases. In addition, novel strategies enable an easier and often straight-forward improvement of enzyme by protein design. These achievements are summarized in this review and examples are given.

1. Introduction

Biocatalysis allows the mild and selective formation of products using (in most cases) isolated enzymes. Of special interest

compared to chemical methods, is the often observed excellent chemo-, regio- and especially stereoselectivity of biocatalysts. In

the past decades, a considerable number of processes have been developed in academia and noteworthy have been industrialized on commercial scale. Many examples are summarized in books1-7) and reviews8,9).

The successful development and implementation of a novel biocatalytic process requires at minimum the (i) availability of a suitable biocatalyst, (ii) methods for enzyme stabilization to ease its application and reuse and (iii) process engineering to deal with the choice of an appropriate reaction system (aqueous or solvent system, batch or continuous, packed-bed or membrane reactor etc.) and with the up- and downstream processing.

2. Accessing Biodiversity

The traditional method to identify new enzymes is based on screening of e.g. soil samples or strain collections by enrichment culture for which many impressive examples can be found in literature10,11), and general references cited above. Once a suitable biocatalyst is identified, strain improvement as well as cloning and expression of the encoding gene is usually performed to enable production at large scale. One advantage of this method is that it is confirmed from the initial identification of a strain with desired activity, that the substrate of interest is indeed converted into the desired product. This differs from the approaches outlined below, where sequence homology is the starting point and hence it remains unclear until the enzyme is obtained whether it indeed converts the substrate to product.

As a disadvantage, classical screening accesses only a very tiny fraction of the biodiversity. Indeed, the number of culturable microorganisms from a sample is estimated to 0.001-1% depending on their origin12,13). In turn, more than 99% of the biodiversity escaped the efforts of scientists in the past to identify novel enzymes only because the microorganisms can not be cultivated.

More recently, new strategies have been developed to include the plethora of ‘nonculturable’ biodiversity in biocatalysis: (i) the metagenome approach and (ii) sequence-based discovery.

Basically, in the metagenome approach, the entire genomic DNA from uncultivated microbial consortia (i.e. soil samples) is directly extracted, cloned and expressed. Microbial cells are lysed to yield high molecular weight DNA, which is then purified followed by standard cloning procedures. After propagation the DNA is usually expressed in easily cultivable surrogate host cells like Escherichia coli. These are then subjected to screening or selection procedures to identify distinct enzymatic activities14-17). The major advantage of this approach is that not only huge numbers of new biocatalysts can be found. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that new subclasses of enzymes can be identified, which show a very broad evolutionary diversity and thus the chance to identify biocatalysts with unique properties is substantially increased. In addition, the identified enzymes are already recombinantly expressed and thus in principle available at large scale. Disadvantages are that logically only those biocatalysts can be found, which can be expressed in the host organism and do not escape the activity tests.

One impressive example is the discovery of > 130 novel nitrilases from more than 600 biotope-specific environmental DNA libraries18), compared to less than 20 nitrilases known so far, which were isolated by classical cultivation methods. The application of these novel nitrilases in biocatalysis revealed, that 27 enzymes afforded mandelic acid in >90% ee in a dynamic kinetic resolution and one nitrilase afforded (R)-mandelic acid in 86% yield and 98% ee. Also, aryllactic acid derivatives were accepted at high conversion and selectivity. The best enzyme gave 98% yield and 95% ee for the (R)-product19) and 22 enzymes gave the opposite enantiomer with 90-98% ee. The most effective (R)-nitrilase was later optimized by directed evolution to withstand high substrate concentrations while maintaining high enantioselectivity20).

Sequence-based discovery is increasingly attractive with the tremendously growing knowledge base (for lipases, epoxide hydrolases and dehalogenases, see for example, http://www.led.uni-stuttgart.de) built from sequencing singular genes, whole genomes and even biotopes. Once new sequences are found, the cloning of the encoding genes is straightforward either by a PCR-based approach amplifying known open reading frames or by the introduction of necessary mutations in already cloned homologous enzyme genes. Furthermore, synthetic genes can be now ordered at very low price from various suppliers. This has the advantages, that the original strain does not need to be obtained from a strain collection (or even isolated from animal, human or plant tissue), the use of pathogenic or difficult-to-grown microorganisms is circumvented, and the gene sequence can be easily adapted to the codon usage and expression system of the host strain.

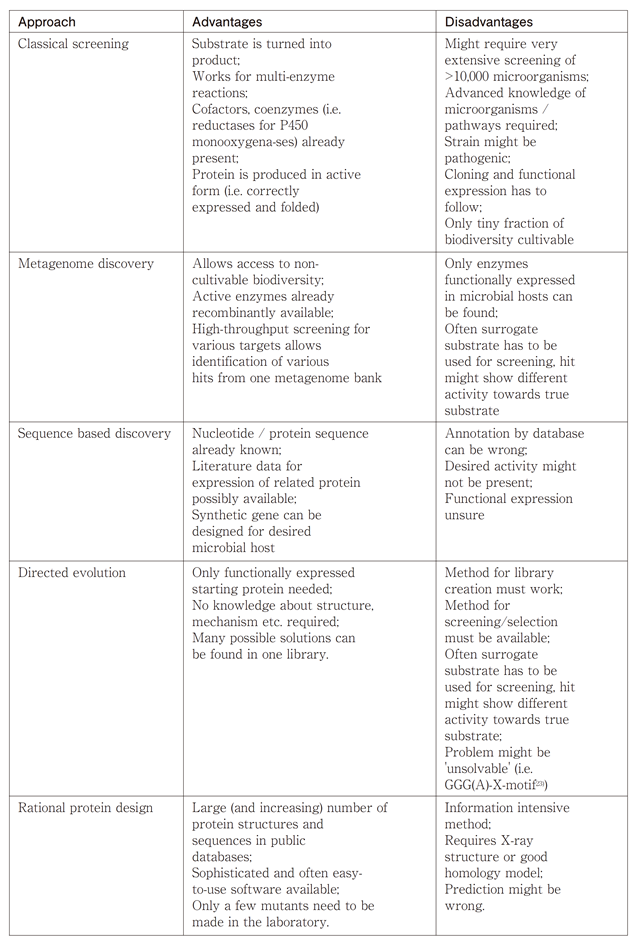

The different approaches to access biodiversity and improve enzymes are given in Table 1. Recent progress in protein engineering is summarized in a book21) and future perspectives can be found in a recent review22).

Table 1 Comparison of different approaches to identify suitable biocatalysts.

3. Strategies to Improve Biocatalysts

Most applications of enzymes in biocatalysis do not rely on the natural reaction catalyzed by them, but rather use non-natural substrates. In addition, the reaction system (i.e. solvent, molarity, pH, temperature) can differ substantially from the environment in which the enzymes have been evolved for in Nature.

Thus quite often activity, stability, substrate specificity and enantioselectivity need to be improved. Until recently, these limitations were usually overcome by rather classical reaction engineering which includes variation of the reaction system until conditions are found, in which the biocatalyst meets the process requirements. Nowadays, the genes encoding the biocatalyst of interest are cloned and expressed recombinantly. Consequently, variation of the enzyme by changing its amino acid sequence provides another alternative to improve its performance. In principle, two major strategies can be followed: (i) rational protein design, which requires the availability of the three-dimensional structure (or a homology model) necessary to identify type and position for the introduction of appropriate amino acid changes by site-directed mutagenesis or (ii) directed evolution.

Directed evolution emerged in the mid 90's (also called in-vitro or molecular evolution) and is essentially comprised of two steps: first, random mutagenesis of the gene(s) encoding the enzyme(s) and second identification of desired biocatalyst variants within these mutant libraries by screening or selection.

3.1 Directed Evolution

Prerequisites for in-vitro evolution are the availability of the gene(s) encoding the enzyme(s) of interest, a suitable (usually microbial) expression system, an effective method to create mutant libraries and a suitable screening or selection system. Many detailed protocols for this are available from books24,25) and reviews26-28).

3.1.1 Methods to Create Mutant Libraries

A broad range of methods has been developed to create mutant libraries. These can be divided into two approaches, either a non-recombining mutagenesis, in which one parent gene is subjected to random mutagenesis leading to variants with point mutations or recombining methods in which several parental genes (usually showing high sequence homology) are randomized. This results in a library of chimeras rather than accumulation of point mutations.

One challenge in directed evolution experiments is the coverage of a sufficiently large sequence space, i.e. the creation of as many variants as possible. Considering a protein (enzyme) consisting of 200 amino acids. Then the number of possible variants of a protein by introduction of M substitutions in N amino acids can be calculated with the formula 19M[N!/(NM)!M!]. Thus, for two random mutations already more than 7 million variants are possible, with 3 or more substitutions, the creation and screening of a library becomes very challenging.

The most prominent method for the creation of libraries is the error-prone polymerase chain reaction (epPCR) in which conditions are used which lead to the introduction of approximately one mutation per 1000 base pairs29). This is achieved by changing the reaction conditions, i.e. use of Mn2+ salts instead of Mg2+ salts (the polymerase is magnesium-dependent), use of the Taq polymerase from Thermomyces aquaticus, and variations in the concentrations of the desoxynucleotides. Another approach utilizes mutator strains, e.g. the Escherichia coli derivative Epicurian coli XL1-Red, lacking DNA repair mechanisms30). Introduction of a plasmid bearing the gene encoding the protein of interest leads to mutations during replication. Both methods introduce point mutations and several iterative rounds of mutation followed by identification of best variants are usually required to obtain a biocatalyst with desired properties.

Alternatively, methods of recombination (also referred to as sexual mutagenesis) can be used. The first example was the DNA (or gene-) shuffling developed by Stemmer, in which DNAse degrades the gene followed by recombination of the fragments using PCR with and without primers31). This process mimics natural recombination and has been proven in various examples as a very effective tool to create desired enzymes. More recently, this method was further refined and termed DNA family shuffling or molecular breeding enabling the creation of chimeric libraries from a family of genes. Various other methods to create mutant libraries can be found in reviews28,32).

Recently, combinations of directed evolution and rational design have been proposed, which have been named semi rational design or rational evolution, but the term focused directed evolution might be more suitable. This includes methods such as Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis (ISM)33), and CASTing (Combinatorial Active-Site Saturation Test)34,35). Both methods rely on the protein structure, but instead of distinct point mutations, several amino acids (usually near the catalytically active site in a radius of ~10 Å) are subjected to simultaneous random mutagenesis. This allows covering many more mutations and also includes cooperative effects of several neighbouring point mutations. At the same time, the screening efforts are substantially reduced compared to a classical directed evolution approach mutating the entire protein. Researchers at Codexis used a similar approach (ProSAR), which in comparison to CASTing, is 3D-structure or homology model-independent and this resulted in a substantial improvement in catalytic function36).

3.1.2 Assay Systems

The major challenge in directed evolution is the identification of desired variants within the mutant libraries. Suitable assay methods should enable a fast, very accurate and targeted identification of desired biocatalysts out of libraries comprising 104~106 mutants. In principle, two different approaches can be applied: Screening or selection.

Selection

Selection-based systems have been used traditionally to enrich certain microorganisms. For in vitro evolution, selection methods are less frequently used as they usually can only be applied to enzymatic reactions which occur in the metabolism in the host strain. On the other hand, selection-based system allow a considerably higher throughput compared to screening systems (see below). Often, selection is performed as a complementation, i.e. an essential metabolite is produced only by a mutated enzyme variant. For instance, a growth assay was used to identify monomeric chorismate mutases. Libraries were screened using media lacking L-tyrosine and L-phenyl alanine37). Mutants of an esterase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (PFE) produced by directed evolution using the mutator strain Epicurian coli XL1-Red were assayed for altered substrate specificity using a selection procedure38). Key to the identification of improved variants acting on a sterically-hindered 3-hydroxy ester - which was not hydrolyzed by the wild-type esterase - was an agar plate assay system based on pH-indicators, thus leading to a change in color upon hydrolysis of the ethyl ester. Parallel assaying of replica-plated colonies on agar plates supplemented with the glycerol derivative of the 3-hydroxy ester was used to refine the identification, because only E. coli colonies producing active esterases had access to the carbon source glycerol, thus leading to enhanced growth and in turn larger colonies. By this strategy, a double mutant was identified, which efficiently catalyzed hydrolysis38).

Screening

Much more frequently used are screeningbased systems (not to be confused with the use of the term ‘screening’ for the identification of microorganisms). Due to the very high number of variants generated by directed evolution, common analytical tools like gas chromatography and HPLC are less useful, as they are usually too time-consuming. Also highthroughput GC-MS or NMR techniques have been described, but these require the availability of rather expensive equipment and in case of screening for enantioselective biocatalysts also the use of deuterated substrates. In addition phage display, ribosome display and FACS have been used to screen within mutant libraries. Although they allow to screen mutant libraries in the order of >106 variants, they are hardly generally applicable.

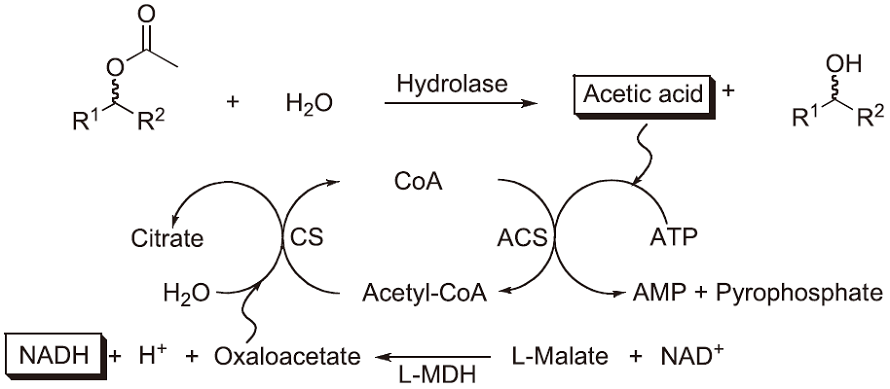

The most frequently used methods are based on photometric and fluorimetric assays performed in microtiter plate (MTP)-based formats in combination with high-throughput robot-assistance. They allow a rather accurate screening of several 10 000 variants within reasonable time and provide sufficient information about the enzymes investigated, i.e. activity by determining initial rates or endpoints and stereoselectivity by using both enantiomers of the compound of interest. For the determination of lipase/esterase activity and enantioselectivity, we developed an assay, in which acetates can be directly used as ‘true’ substrate. This method is based on a commercially available "acetic acid" test (R-Biopharm GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany), which couples the hydrolysis of acetates with an acetate-dependent enzymatic cascade leading to the stoechiometric formation of NADH39) (Scheme 1). If enantiomerically pure chiral (R)- and (S)-acetates are used in separate experiments but using the same enzyme variant, the method allows the determination of the (apparent) enantioselectivity. It was successfully used to identify an esterase variant with high enantioselectivity in the synthesis of 3-butyn-2-ol40). Several elegant screens were developed by Reymond and coworkers, which are based on the release of resorufin, coumarin or the formation of adrenochrome and avoid the often observed instability of the enzyme substrate41). Disadvantages are the need for synthesis of the specifically designed substrates and that only end-point measurements are possible rather than quantification of enzyme kinetics. A very simple and carefully optimized assay (Quick E) for hydrolases is based on the use of pH indicators and allows the rather accurate determination of enantioselectivity starting from the true substrate42,43).

4. Examples

The majority of industrially used enzymes are hydrolases (65%) and thus many examples of evolved hydrolases can be found in literature. One of the first example was an esterase variant from Bacillus subtilis (BsubpNBE) with a 150 times higher activity in 15% DMF compared to the wild-type, created by combining epPCR and shuffling. The enzyme is therefore applicable for the deprotection of a precursor in the production of the antibiotic Loracarbef in the presence of DMF as cosolvent44). A related esterase (BS2), which differs only by 11 amino acids from BsubpNBE, was evolved by rational design in my group and the enantioselectivity towards the tertiary alcohol 2-phenyl-3-butin-2-yl acetate could be increased six-fold to E=19, and towards linalyl acetate inverted from (R) to (S) preference with E=645). In a later study, this mutant (G105A) showed a good enantioselectivity towards 2-phenyl-3-butin-2-yl acetate (E=54) in 20% v/v DMSO, and an E-value of >100 towards the trifluoromethyl analogue46). Another mutant E188D gave similar high enantioselectivity towards both substrates as well as a series of other tertiary alcohol acetates47). Using a focused random approach we were also able to invert the enantioselectivity48). While screening with the acetate assay described above, a double mutant (E188W/M193C) with an (S)-preference and an E-value of~70 towards 1,1,1-trifluoro-2-phenylbut-1-yn-3-ol was identified. Notably, the single mutants E188W or M193C, which could have also been obtained by random mutagenesis, show only E=16 for the (S)-enantiomer or low (R)-selectivity, respectively, and that only the combination, which were rather unlikely be obtained by ‘normal’ random mutagenesis, results in the substantial inversion of enantioselectivity. This synergistic manner is thus an excellent argument for using focused directed evolution.

Shortly after the first evolved esterase from the Arnold group, directed evolution of a lipase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa was reported by Reetz and coworkers. The initial enantioselectivity in the kinetic resolution of 2-methyl-decanoic acid p-nitrophenyl ester (MDA) was E=1.1 (in favor of the (S)-acid), and after four rounds of epPCR an E=11 was obtained. Further improvements were achieved by combining mutations, using DNA shuffling and cassette random mutagenesis resulting in variants with high and practically useful enantio selectivities49-51).

In my group, we evolved an esterase from Pseudomonas fluorescens (PFE-I) first using the mutator strain E. coli XL-1 Red52) followed by epPCR and HTS with the acetic acid assay, which resulted in a mutant with excellent selectivity for synthesis of important building block 3-butyn-2-ol40).

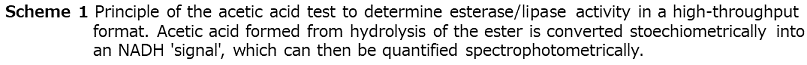

The catalytic function of a halohydrin dehalogenase (HHDH) from Agrobacterium radiobacter was improved by ProSAR-driven evolution to obtain ethyl (R)-4-cyano-3-hydroxybutyrate, which is also used in the synthesis of atorvastatin (Lipitor) (Scheme 2)36). The new enzyme had a 4000-fold volumetric productivity in the cyanation process compared to the wildtype.

Scheme 2 Synthesis of a key precursor of Lipitor using a halohydrin dehalogenase (HHDH).

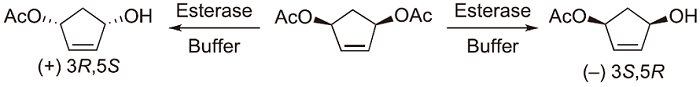

In addition to the example given in the introduction, we could show that the metagenome is a very rich source of novel biocatalysts even showing opposite enantioselectivity. For instance, we found 35 esterases / lipases originating from metagenome sources to be active and selective in the asymmetric hydrolysis of cis-3,5-diacetoxycyclopent-1-ene (Scheme 3)53). Subsequent analytical and laboratory scale biocatalysis reactions identified three enzymes showing excellent (-)-preference and one esterase with excellent (+)-selectivity. In another project, we were able to identify several hydrolases from the metagenome to be useful in the kinetic resolution of esters of tertiary alcohols54).

As stated in the introduction, sequencebased discovery of enzymes is a very useful and straightforward approach. However, the annotation of newly identified and deposited sequences is based on homology to known proteins and hence this can lead to misleading classification of an enzyme. For instance, we had identified an open reading frame encoding an esterase in the sequence data derived from Ps. fluorescens. Further genes up- and downstream of this esterase-encoding orf showed homology to an oxidoreductase (in fact: an alcoholdehydrogenase) and to a ’cyclohexanone monooxygenase‘55). This type of enzyme belongs to the so-called Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases (BVMO), which catalyze the formation of esters or lactones from ketones using molecular oxygen. Indeed, we could show, that the esterase preferentially hydrolyzes lactones such as ε - caprolactone - the product of a BVMO-catalyzed oxidation of cyclohexanone. Unfortunately, we were unable to see convincing conversion of cyclic ketones. Later, we found by identification of further orfs, that this BVMO belongs to a new class of enzymes, which convert aliphatic ketones (such as 2-octanone) to the corresponding esters, but NOT cyclic ketones56,57). Thus, the annotation of the encoding gene was wrong with respect to substrate specificity (but not to function as a BVMO), which caused a substantial delay and extra work on this project. Note, that the BVMO-encoding gene was later annotated as phenylacetone monooxygenase, but also this is not a substrate for this specific BVMO. In another example Hua and coworkers confirmed that the substrate of an unknown protein - of which the sequence was found by genome mining in a database - can be predicted by examination of flanking open reading frames leading to the discovery of a mandelonitrile hydrolase58).

5. Conclusions and Perspective

The strategies developed in the past decade for the discovery and design of novel biocatalysts clearly underline that protein engineering became a mature technique to identify and create desired enzymes for a given application within reasonable short development times. Moreover, new tools such as the metagenome approach and sequence-based discovery substantially ease the access to novel enzymes without the need of classical enrichment cultures. This not only enabled the discovery of broad sets of useful biocatalyts, but also provides rapid access to already recombinant enzyme, which in turn facilitates upscaling of the reaction of interest.

6. References

1) Liese, A., Seelbach, K., Wandrey, C., Industrial Biotransformations, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2000.

2) Drauz, K., Waldmann, H., Enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis, 2nd ed., VCH, Weinheim, 2002.

3) Bornscheuer, U. T., Kazlauskas, R. J., Hydrolases in Organic Synthesis - Regioand Stereoselective Biotransformations, 2nd ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2006.

4) Faber, K., Biotransformations in organic chemistry, 4ed., Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, 2004.

5) Patel, R. N., Biocatalysis in the Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Industries, CRC Press, London, 2006.

6) Buchholz, K., Kasche, V., Bornscheuer, U. T., Biocatalysts and Enzyme Technology, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005.

7) Bommarius, A. S., Riebel, B. R., Biocatalysis, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004.

8) Schoemaker, H. E., Mink, D., Wubbolts, M. G.: Science, 299, 1694 (2003).

9) Breuer, M., Ditrich, K., Habicher, T., Hauer, B., Keßeler, M., Stürmer, R., Zelinski, T.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 43, 788 (2004).

10) Ogawa, J., Shimizu, S.: Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 13, 367 (2002).

11) Asano, Y.: J. Biotechnol., 94, 65 (2002).

12) Lorenz, P., Liebeton, K., Niehaus, F., Schleper, C., Eck, J.: Biocat. Biotransf., 21, 87 (2003).

13) Miller, C. A.: Inform, 11, 489 (2000).

14) Short, J. M.: Nature Biotechnology, 15, 1322 (1997).

15) Uchiyama, T., Takashi, A., Ikemura, T., Watanabe, K.: Nature Biotechnology, 23, 88 (2005).

16) Handelsman, J.: Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 68, 669 (2004).

17) Handelsman, J.: Nature Biotechnology, 23, 38 (2005).

18) Robertson, D. E., Chaplin, J. A., DeSantis, G., Podar, M., Madden, M., Chi, E., Richardson, T., Milan, A., Miller, M., Weiner, D. P., Wong, K., McQuaid, J., Farwell, B., Preston, L. A., Tan, X., Snead, M. A., Keller, M., Mathur, E., Kretz, P. L., Burk, M. J., Short, J. M.: Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 70, 2429 (2004).

19) DeSantis, G., Zhu, Z., Greenberg, W. A., Burk, M. J.: J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 9024 (2002).

20) DeSantis, G., Wong, K., Farwell, B., Chatman, K., Zhu, Z., Tomlinson, G., Huang, H., Tan, X., Bibbs, L., Chen, P., Kretz, K., Burk, M. J.: J. Am. Chem. Soc., 125, 11476 (2003).

21) Lutz, S., Bornscheuer, U. T., Protein Engineering Handbook, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009.

22) Bornscheuer, U. T., Kazlauskas, R. J.: Nat. Chem. Biol., 5, 526 (2009).

23) Henke, E., Pleiss, J., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 41, 3211 (2002).

24) Arnold, F. H., Georgiou, G., Directed Enzyme Evolution: Screening and Selection Methods, Humana Press, Totawa, 2003.

25) Arnold, F. H., Georgiou, G., Directed Evolution Library Creation: Methods and Protocols, Humana Press, Totawa, 2003.

26) Reetz, M. T.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 5716 (2004).

27) Bornscheuer, U. T.: Biocat. Biotransf., 19, 84 (2001).

28) Neylon, C.: Nucleic Acid Res., 32, 1448 (2004).

29) Cadwell, R. C., Joyce, G. F.: PCR Meth. Appl., 2, 28 (1992).

30) Bornscheuer, U. T., Altenbuchner, J., Meyer, H. H.: Biotechnol. Bioeng., 58, 554 (1998).

31) Stemmer, W. P.: Nature, 370, 389 (1994).

32) Kurtzman, A. L., Govindarajan, S., Vahle, K., Jones, J. T., Heinrichs, V., Patten, P. A.: Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 12, 361 (2001).

33) Reetz, M. T., Carballeira, J. D., Vogel, A.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 45, 7745 (2006).

34) Reetz, M. T., Carballeira, J. D.: Nat. Protoc., 2, 891 (2007).

35) Reetz, M. T., Wang, L. W., Bocola, M.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 45, 1236 (2006).

36) Fox, R. J., Davis, S. C., Mundorff, E. C., Newman, L. M., Gavrilovic, V., Ma, S. K., Chung, L. M., Ching, C., Tam, S., Muley, S., Grate, J., Gruber, J., Whitman, J. C., Sheldon, R. A., Huisman, G. W.: Nature Biotechnol., 25, 338 (2007).

37) MacBeath, G., Kast, P., Hilvert, D.: Science, 279, 1958 (1998).

38) Bornscheuer, U. T.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 37, 3105 (1998).

39) Baumann, M., Stürmer, R., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 40, 4201 (2001).

40) Schmidt, M., Hasenpusch, D., Kähler, M., Kirchner, U., Wiggenhorn, K., Langel, W., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Chem. Bio. Chem., 7, 805 (2006).

41) Reymond, J. L., in, Enzyme Assays, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005.

42) Janes, L. E., Löwendahl, C., Kazlauskas, R. J.: Chem. Eur. J., 4, 2324 (1998).

43) Horsman, G. P., Liu, A. M. F., Henke, E., Bornscheuer, U. T., Kazlauskas, R. J.: Chem. Eur. J., 9, 1933 (2003).

44) Moore, J. C., Arnold, F. H.: Nature Biotechnol., 14, 458 (1996).

45) Henke, E., Bornscheuer, U. T., Schmid, R. D., Pleiss, J.: Chem. Bio. Chem., 4, 485 (2003).

46) Heinze, B., Kourist, R., Fransson, L., Hult, K., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Prot. Eng. Des. Sel., 20, 125 (2007).

47) Kourist, R., Bartsch, S., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Adv. Synth. Catal., 349, 1393 (2007).

48) Bartsch, S., Kourist, R., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 47, 1508 (2008).

49) Liebeton, K., Zonta, A., Schimossek, K., Nardini, M., Lang, D., Dijkstra, B. W., Reetz, M. T., Jaeger, K. E.: Chem. Biol., 7, 709 (2000).

50) Reetz, M. T., Wilensek, S., Zha, D., Jaeger, K. E.: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 40, 3589 (2001).

51) Reetz, M. T., Puls, M., Carballeira, J. D., Vogel, A., Jaeger, K. E., Eggert, T., Thiel, W., Bocola, M., Otte, N.: ChemBioChem, 8, 106 (2007).

52) Henke, E., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Biol. Chem., 380, 1029 (1999).

53) Brüsehaber, E., Böttcher, D., Liebeton, E., Eck, J., Naumer, C., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 19, 730 (2008).

54) Kourist, R., Krishna, S. H., Patel, J. S., Bartnek, F., Weiner, D. W., Hitchman, T., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Org. Biomol. Chem., 5, 3310 (2007).

55) Khalameyzer, V., Fischer, I., Bornscheuer, U. T., Altenbuchner, J.: Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 65, 477 (1999).

56) Kirschner, A., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 45, 7004 (2006).

57) Kirschner, A., Altenbuchner, J., Bornscheuer, U. T.: Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 75, 1095 (2007).

58) Zhu, D., Mukherjee, C., Biehl, E. R., Hua, L.: J. Biotechnol., 129, 645 (2007).